Neil Fisher enjoys following in the footsteps of the 17th-century composer in his 450th anniversary year

What’s the soundtrack to Venice? There’s the lazy cry of the gondolier, the bored whine of a teenage tourist, or — up a harmonic notch — Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the piece that launched a thousand call centres and is piped out in many a Venetian piazza while grinning students sporting frock coats and wigs try to entice you into naff musical spectacles.

Vivaldi was a Venetian composer, it’s true. He was not, however, the Venetian composer. That honour should go to Claudio Monteverdi, whose 30 years in the city in the first half of the 17th century coincided not just with Venice’s political zenith, but with the transition from the Renaissance to the baroque — an evolution with Monteverdi at its heart. As choirmaster of St Mark’s Cathedral, Monteverdi wrote the Masses that would celebrate the city’s naval triumphs or console its people after defeat. Meanwhile, the stage works he wrote in Venice effectively created the art form of opera as it exists today: naughty, flirty entertainment, open to anyone who could buy a ticket.

This year the world is celebrating Monteverdi. It’s the composer’s “450th birthday” and there will be performances galore of Monteverdi’s Vespers, his dazzling 1610 collection of liturgical settings, extra helpings of his motets and madrigals, and a bumper crop of performances of his three surviving operas. Venice is going the full Monteverdi too. The city’s celebrated opera house, La Fenice, will host all the operas, there will be conferences of Monteverdi experts, and many of the composer’s Masses will pop up in churches across the city. And so I hit La Serenissima hoping to walk in the composer’s footsteps or, knowing Venice, occasionally paddle in them.

The task is harder than it seems. Venice is a living museum, right? Si, e no. Monteverdi lived and worked in a building adjacent to St Mark’s, but, over centuries, so have lots of other choirmasters and they didn’t even get a suite.

The maestro di cappella wrote his masterpieces in one room, where he also slept, and the present apartment block (now used by clerics) is out of bounds unless you have a pious reason to be nosing around.

Never mind — there’s always the cathedral itself. You’re halfway towards understanding Monteverdi’s choral music — which conductors like to bolster with great brass displays from cornetts (antique trumpets) and sackbuts (trombones) — when you see the church’s strange domes and galleries, lit with the glitter of a gazillion tesserae. The spatial effects of Monteverdi’s largest-scale music — he often requires two choirs to field different harmonic lines — are inspired, and pretty much necessitated, by the idiosyncratic shape of the church interior.

Queueing with the tourist hordes is one way of getting in, but a more peaceful route, if you don’t mind a bit of sermonising in Italian, is to come for Sunday Mass (admission free). Monteverdi’s present successor, the choirmaster Marco Gemmani, has reinvigorated St Mark’s choir and plans to celebrate Monteverdi this year. He is reconstructing a lost Mass for the Feast of the Assumption in August, and in October the cathedral will host the Vespers.

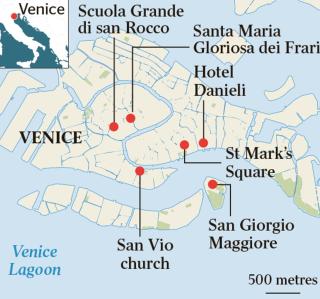

A vaporetto (water bus) takes me to another stop on the trail. San Giorgio Maggiore is a hidden treasure. This little island is home to a Palladio church with a campanile that offers a great view over the lagoon. The church would have been only a few decades old when Monteverdi arrived in Venice, and we know that he practised the organ here before his audition at the cathedral. It’s not a bad place to brush up on your scales; Monteverdi would have had the company of two majestic Tintorettos, one of which, a Last Supper, is full of dazzling detail.

Back in the throng, I work my way through the Dorsoduro area. I drop into the tiny church of San Vio, where Monteverdi got himself into what could have been seriously hot water with the Venetian Inquisition. Around 1623 he was anonymously denounced for insulting the doge and clergy: the allegation was that, while rehearsing another of his choirs in San Vio, he had lashed out against his civic and clerical bosses, calling them pantaloni and coglioni; literally, “trousers” and “testicles” (“stuffed shirts” might be the best translation). Whether or not it was true, the Inquisition took no further action.

Perhaps they knew Monteverdi’s tunes were too good to lose. At the Scuola Grande di san Rocco I avoid the audio guide and plug myself into Monteverdi’s serene motet, Beatus Vir, which was first performed in the Scuola’s spectacular Sala dell’Albergo, decked with Tintorettos on the walls and ceiling. The Scuola will host a performance of Beatus Vir in July, and the adjoining San Rocco church will be a base for Monteverdi performances this summer.

It’s appropriate that music is rep- resented at Monteverdi’s resting place in the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Fair enough, you come here for Titian’s glorious Assumption of the Virgin, but tucked into a chapel is the tomb of the composer, marked by a stone plaque and a bust and watched over by a painted altarpiece featuring two heavenly lutenists.

After all this reverence, I need some R&R. Helpfully, this is easily managed at Palazzo Dandolo. The palace is now better known as the Hotel Danieli, a five-star mansion where Maria Callas and Greta Garbo have stayed. In one of the two grand piano nobile foyers on the first and second floors, it’s also where Monteverdi’s groundbreaking operatic madrigal, Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, was first performed, as part of a wedding celebration in 1624 hosted by Monteverdi’s patron Girolamo Mocenigo. Even better, the Danieli has a rooftop terrace where you can sip a Bellini in comfort (Venetian mixologists have yet to invent the Monteverdi) and so pay homage to the maestro at perfect ease. That is, until I get the bill — and let loose an aria of such astonished fury that it would make even Monteverdi blush.

Need to know

Neil Fisher was a guest of the San Clemente Palace Hotel, which is offering a package of two nights’ accommodation, dinner and opera tickets for John Eliot Gardiner’s performances in La Fenice between June 17 and 19. Prices start at £1,540 (kempinski.com). Easyjet has return flights to Venice from about £60 (easyjet.com). I-escape.com has a selection of small boutique hotels/B&Bs from about £100 a night. Gardiner conducts Monteverdi’s operas in Colston Hall, Bristol, on May 8 and 28 (colstonhall.org) and at the Edinburgh International Festival, August 14-17 (eif.co.uk)