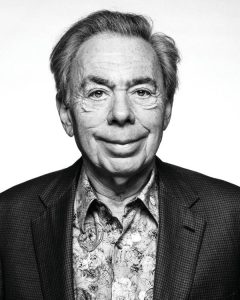

Andrew Lloyd Webber has a record four musicals running simultaneously on Broadway. So why doesn’t he get more love in his own country, asks Josh Glancy

Here’s a good piece of trivia: what film or play has the highest box-office takings in history? It’s not Titanic, or The Lord of the Rings, ET or Avatar. It’s not even Star Wars. The answer, by a quite astonishing distance, is Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera, coming in at $6bn, or roughly the same as the first six Star Wars films put together. It’s been running on Broadway for 29 years and in London for 31. Nothing else comes close.

Lloyd Webber’s musicals are relentlessly, impossibly popular. As of February he has four of them showing simultaneously on Broadway: Cats, The Phantom of the Opera, School of Rock and a reboot of Sunset Boulevard, with Glenn Close reprising her famous role as the faded Hollywood diva Norma Desmond. He shares this record only with the great Rodgers and Hammerstein, and it hasn’t been done for 60 years.

We live in an age of Snapchat memes and 15-second videos of people with superimposed rabbit ears eating carrots. Yet, every evening, thousands in both London and New York still pay exorbitant prices (up to $300 for a premium ticket on Broadway) to cram into giant, faded music palaces and be regaled by Christine Daaé and Macavity the Mystery Cat.

Lloyd Webber, then, is in many ways one of the great pop-culture figures of the modern age. Generations of children have grown up listening to his music, often set to lyrics by Tim Rice. He has written and produced, but his essence is a composer with a unique ability to intertwine meaningful stories with memorable showbiz tunes. Yet somehow, he never quite seems to have attained national treasure status.

I meet him for the first time in the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway, where he cuts a diminutive figure, sitting alone in the stalls wrapped up in a giant furry black parka, to protect him from the biting New York cold.

What, I wonder, is the secret of his work’s extraordinary durability? Why do successive generations continue to fall in love with his musicals?

“There’s no one answer, of course,” he says after a long pause. “But I think the story’s probably the most important thing. I think School of Rock or Sunset Boulevard work because they are simple, primal tales, very good stories. Joseph [and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat] works because it’s a very simple story. A great story can carry a musical. But a great score without a great story can struggle — apart from Cats, of course.”

Once you get past the initial hint of reserve and pomposity, it’s hard not to like Lloyd Webber. I can honestly say I have never met anyone as culturally prominent who is so resolutely uncool. He’s a music geek with a taste for high camp. He dresses a little oddly, he sounds frightfully, anachronistically posh, and he’s a dyed-in-the-wool Tory. It’s not exactly rock’n’roll, but there’s also refreshingly little artifice. No aspirations of hipness or prefab luvvie politics. He’s successful not because he’s created a cool brand, but because he has that rare combination of deep talent and an obsessive work ethic.

Lloyd Webber’s deepest passions are musical theatre and historical buildings — his childhood dream was to become England’s chief inspector of ancient monuments. On the rare occasions he takes a day off, his idea of a good time is nerding out over architecture. “My real relaxation is looking at buildings, that’s what I love,” he says. “A lovely day in Margate and Canterbury and I’m away.” His other passion is also “deeply unfashionable”: Victorian and pre-Raphaelite art, of which he has an extraordinary collection that went on show at the Royal Academy in 2003. There are bright and colourful works by Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, all of which reflect Lloyd Webber’s own love of history and beauty. The art critic Jonathan Jones described seeing the collection as “like waking up in the grandest, most pointless BBC costume drama of all time”.

Despite his prodigious success, there seems to be a vulnerability to Lloyd Webber that you don’t often find among those who have dominated their field. The people close to him are unusually protective, which I discover in the evening after our interview when he invites me to a party being held in his honour by the American Theatre Wing, to mark his remarkable quadruple-header of Broadway productions before the premiere of Sunset Boulevard.

It’s a typically camp Broadway affair: velvet tuxedos and champagne and lots of small old men squiring very tall and beautiful young women. Famous producers and art directors abound; there are actors you recognise from Mad Men. But I also meet his racehorse manager, Simon Marsh, who has flown over from Berkshire especially. Wilfred Frost, son of David, is there: Lloyd Webber has kept in touch with the television impresario’s children since the death of his old friend Frost in 2013. I have a chat with Jan, Lloyd Webber’s longtime personal assistant, and his wife, Madeleine. All of them speak fondly and loyally of Lloyd Webber as a friend, employee and partner. But there’s a distinct note of defensiveness too. They’re tired of bitchy profiles in British newspapers that call him ugly, tacky or weird.

I think they’re right to be. It’s easy to take the mickey out of Lloyd Webber, but that’s a playground instinct. If his naffness has prevented him from becoming a national treasure, well, that’s our oversight. He provided the soundtrack to most of our childhoods. He’s the creative force behind a million road-trip singalongs and birthday trips to theatreland. Aided by the marketing genius of his friend Cameron Mackintosh, he pretty much invented the modern British musical. Mackintosh, he says, is the only Brit he’s ever met who shares his “passion” and “single-mindedness” about musical theatre.

On Broadway they either revere Lloyd Webber’s work or they despise it, depending on who you ask. But no one ignores it. On the billboards outside the Winter Garden, his name is projected in bright lights, making it very clear: this is a Lloyd Webber show.

In Britain, though, we’re still a bit snooty about the whole thing. I wonder how frustrating this is. “I still think that somewhere engrained in Britain is the thought that ‘we don’t do musicals’,” he says. “It’s very much considered to be the American form. Whereas here in New York, you know, everybody lives, breathes and talks them.”

As for Lloyd Webber, he has been living and breathing musicals since he was a child. Born into a musical, middle-class family, he was composing his own pieces before he was 10 and putting on “productions” in the living room with his brother, Julian, a cellist. He studied at Westminster and won a place at Oxford to read history. But, with the rare freedom granted to someone who knows exactly what they should be doing in life, he quickly abandoned Oxford and moved to London to study music.

What came next is the stuff of showbiz legend. Still a teenager, Lloyd Webber received a letter from a 21-year-old law student called Tim Rice, expressing admiration for his work and suggesting the two meet up. A couple of years later the pair were commissioned to write a musical for Colet Court prep school in London. The result was Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat, which will turn 50 next year.

His father taught at the Royal College of Music, but the young Lloyd Webber’s populist tendencies took him away from his family’s high musical tone and from the fashions of the time.

He ploughed on regardless, though, and his father supported him, seeing his son pursue his fondest ambition in a way that he’d been unable to. “Dad loved musicals, and he was overjoyed that I did,” he says. “He was from a very working-class background and got scholarships everywhere. So to not pursue a serious music career would have been like letting the side down. But I think he really, really could have had a major career as a film score composer.”

Lloyd Webber’s main home has always been England, where he splits his time between a grand Hampshire estate, Sydmonton Court, and a flat in west London. He says he doesn’t have much money in the bank, mostly because he spends it all on beautiful things: theatres in the West End, a renowned wine cellar, his art collection and his other passion, racehorses. In 2012 his filly The Fugue won the Nassau Stakes at Goodwood. He cashed in after by reportedly selling its mother to the Qatari royal family for £1.7m.

His professional home is still the West End, where he owns a number of venues and first made his name as the 22-year-old prodigy who composed Jesus Christ Superstar. But it is New York where he has really been given his due. “They seem to feel that I’m part of the community here, you know …” he says.

He recalls coming to New York a couple of years ago after a horrifying period. He had survived a virulent form of prostate cancer, which was followed by a routine back operation that went wrong and led to 14 procedures under general anaesthetic. The struggle to survive drew him into a deep depression and helped convince him of the wisdom of assisted dying.

But the first thing he did once he recovered, was, inevitably, another musical. “As soon as I was well again, I thought, ‘Right, back to business,’ ” he says.

It’s hard not to like Lloyd Webber, but I can honestly say I have never met anyone as culturally prominent who is so resolutely uncool

He’d been without a truly successful musical in more than a decade, so it was far from a sure thing when he announced that he would debut a musical, School of Rock, on Broadway. “There was an extraordinary feeling here that they actually wanted to embrace it,” he smiles. It was a hit.

Lloyd Webber’s always done his best to change Britain’s mind about musicals. His latest gambit is turning the St James Theatre in the West End into a “breeding ground” for new musicals, somewhere young writers can go to try out material and find collaborators.

“We’ve got to get young writers in Britain interested in the musical again,” he says, pointing out that in the past year only two new productions have opened in the West End, which has fallen far behind Broadway. One of them, Groundhog Day, was a try-out for Broadway. The other was by Gary Barlow. “There are 13 new musicals opening on Broadway this season,” he adds. “And the reason is that there are so many places in America where you get an opportunity to work and develop material.”

The obvious, monumental example is the success of Hamilton, the hip-hop interpretation of the life of the American statesman and founding father Alexander Hamilton, which has been perhaps the biggest musical phenomenon ever on Broadway. Lloyd Webber liked it so much that he befriended its creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda. But Hamilton, he points out, was six years in development. “Lin wanted to start it as a concept album like Jesus Christ Superstar, and nobody was interested. These things need time.” He hopes its success, along with that of the musical film La La Land, will be a springboard to get people in Britain “back into thinking about musicals again”.

Hamilton, he says, reminds him of The Phantom of the Opera. They are entirely different in style, but both are rare examples of musicals where every single element has come together perfectly. “The set, the design, the choreography, it all coalesces and the whole thing is 100% right,” he says. “It’s very unusual. For a musical to really, really happen, a tremendous amount of stars have to collide.”

I think to myself, what would have happened if I’d met Mandy Rice-Davies when I was 24 … Maybe that’s a line of inquiry we won’t go down

He knows this all too well, having had plenty of flops amid the hits. There was The Woman in White (2004), Love Never Dies (2010) and Stephen Ward (2013), a quixotic attempt to put the Profumo affair to music that was panned by critics and audiences alike; it barely ran for four months in the West End. He doesn’t regret it, though, primarily because he got to know Mandy Rice-Davies, the good-time girl at the heart of the Profumo scandal, who was “the most life-enhancing woman” he’d ever met. “The musical should have been about her, really,” he says, reflecting on her death in 2014. “I keep thinking to myself, what would have happened if I’d met Mandy when I was 24 years old?” he says. I laugh nervously. What would have happened? “Maybe that’s a line of inquiry we won’t go down. But I would have loved to have met her, let me tell you that …”

Of course he’s no longer a priapic 24-year-old. Instead he turns 70 next year and is now a grandfather. With £715m of assets, according to the last Sunday Times Rich List. He has been married three times and has five children. Two from his first marriage to Sarah Hugill — Nicholas, 37, and Imogen, 40, who is a political commentator and author based in New York. And three, Alastair, 24, William, 23, and Isabella, 20, from his most recent marriage to Madeleine Gurdon, a retired three-day eventer who used to ride with Princess Anne. The couple met through equestrian pals in Hampshire.

He is “not a great believer in inherited wealth” and doesn’t intend to pass on much of his fortune. His art collection, he believes, should go “somewhere it can be seen”. As for the rest, he thinks inherited money can be a “very, very great damage to a child, to spoon-feed them”. Having to make your own money means there’s “something incredibly wonderful” about your first paycheck. “You know … I’m jolly glad I didn’t have any inherited money.”

That’s about as left-wing as his politics get, though. He sits as a Tory peer in the House of Lords. He was ambivalent about Brexit, but came down narrowly against. Trump, on the other hand, baffles him, for he knows the president from his time in Trump Tower (he bought an apartment there in 1985 for his second wife, the singer Sarah Brightman, who was starring in The Phantom of the Opera on Broadway).

In fact, Trump invited him round for coffee during the primary campaign. The pair discussed Brightman and her voice, which the president is a huge fan of. And of Trump’s unlikely march on the White House, “I got the impression that he was incredibly surprised about it all … He didn’t look like a man who was passionate to become president. He looked like somebody who was going along with it.”

You only need a few minutes with Lloyd Webber to realise that he isn’t likely to slow down as he approaches 70. He recalls walking past the old Clapham Grand Theatre recently, which long ago transitioned from being a playhouse to a nightclub for paralytic Aussie expats. “I go in there and — oh my God, you know, I think let’s write something for this … I just, I’m afraid I just love musicals. I can’t imagine a life without them. So of course I’m going to go on. I love them and that’s what I do.”

The last time I speak to him is on the phone from Barbados, where he has a holiday home. He is recuperating after having Jeremy Clarkson to stay, which he says he’s “getting too old for”. He’s stayed on for a few days to write in peace, but is taking his time over his next project, acknowledging that perhaps his biggest flaw over the years has been to “plough into subjects that weren’t actually right”. The next one he wants to be immaculate.

I suspect he’s got at least one more hit in him, and can’t help but wonder again if he’s been a little shortchanged by the British public. He demurs. “I always feel if in life you’re lucky enough to know what you want to do and make a living out of it, and then if you’re as lucky as I’ve been … well then, you don’t complain.”

Still, surely more people should know that Phantom is bigger than Star Wars? “Yes, maybe,” he says. “But you wouldn’t expect anybody to know that. I mean, why would you? You don’t sort of say ‘bigger than Star Wars’ outside the theatre.” Actually, I’m starting to think that’s exactly what he should do.